- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Uncategorized »

- Discrimination, Inconvenience, and Opportunity

Discrimination, Inconvenience, and Opportunity

When I give Code of Conduct Incident Response workshops, one of the subjects I cover is discrimination. Sometimes there’s an attendee who has questions about “reverse discrimination”. This is a tough subject to pick apart, so this post is a little long.

First, let’s start with a story.

Community Center Blues

I work out at a community center in my town. I choose the community center because it’s one of the few community centers that has a pool. The community center has everything you need to work out: a weight room, treadmills, exercise classes, and, of course, men’s and women’s locker rooms to change and shower.

The community center also has several private changing rooms that are marked as being reserved for families with children, seniors, and people with disabilities. The showers in the private changing rooms are equipped with grab rails and a foldable seat (so people with mobility issues can sit while showering) and two shower nozzles (one at adult height and one at a child’s height).

Like a lot of community centers, the shower is operated with a push button that only allows the water to flow for a specific amount of time. The private changing rooms with a dual shower head have two buttons.

The other day, I noticed a funny thing when I accidentally pushed the lower shower button. The lower shower head ran for a longer time than the upper shower head.

This puzzled me for a moment. Having two shower heads makes sense. Outside of elementary or primary schools, buildings aren’t made for children. Having a shower head at their height with a button within reach gives them independence. It also helps people with mobility issues who are sitting on the bench.

Discrimination vs Inconvenience

But why would the community center make the shower water button for children and people with mobility issues run longer? It’s certainly an inconvenience for taller, able-bodied adults to have to mash a button every 15 seconds when you’re cold, wet, and have soap in your eyes. It might feel unfair to you that the community center wouldn’t make the shower water timer equal for everyone. Maybe it even feels like discrimination against able-bodied adults. “Reverse able-ism” if you will.

I often see this type of conversation come up. People see that a particular group benefits from a policy, or someone makes a space that’s explicitly designed for a particular group of people, and some folks feel left out. Hurt. Angry.

On Equality

“Why can’t we treat everyone equally?” some people might ask. “Why do those people get special treatment?”

You could imagine the great lengths the community center could go to ensure everyone gets an equally pleasant showering experience. Instead of push buttons that provide a timed amount of water, they could install sensors that would turn on the water only when a person was standing or sitting under the shower.

That would create an equal experience… assuming the sensor manufacturer tested their product with people who had a variety of different skin colors.

If you have ever had a problem grasping the importance of diversity in tech and its impact on society, watch this video pic.twitter.com/ZJ1Je1C4NW

— Chukwuemeka Afigbo (@nke_ise) August 16, 2017

Even if an equally effective sensor was installed, it would probably cost the community center tens, maybe hundreds of thousands of dollars to rip up the walls and install sensors and new shower heads and maybe even new water pipes.

All so that able-bodied adults could stop pushing a button every 15 seconds.

Going to all this renovation work in order for all people to have equally pleasant showers seems a bit extreme. After all, lots of buildings provide unequal access to folks. Some buildings only have stairs, and lack elevators or ramps for people who use mobility devices. Theaters often lack closed captioning for people who are hard of hearing, or provide sub-par experiences with closed caption devices that skip lines or obscure the movie.

RT if you prefer open captioning instead of this pic.twitter.com/Tdql6x5FAk

— Nyle DiMarco (@NyleDiMarco) February 18, 2018

Public places could provide an equal experience for all, but that costs time and money to accommodate everyone.

Every day, people make decisions about who gets a better experience, whether it’s at a theater or at a community center. The lack of action to accommodate people with disabilities and people of color builds up over time, with hundreds of thousands of people making small decisions every day that exclude people.

The end result is that every day people with disabilities and people of color are faced with the fact that their lived experience is less important to white, able-bodied people.

Does that sound equal?

Diversity Programs

In order for everyone to have an equally pleasant showering experience, my community center would need to invest in new tech and undertake a giant construction project that would probably inconvenience everyone. The project would likely cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A better use of those community center funds might be to give children free swimming lessons. My town has several different deep rivers that run through it, and it’s legitimate to worry about children drowning.

Maybe the community center could even offer swimming classes to children of color who live in the neighborhood. You might wonder why they would choose to teach that particular group of children to swim. However, once you look at America’s history of race and gender at public pools, it makes sense.

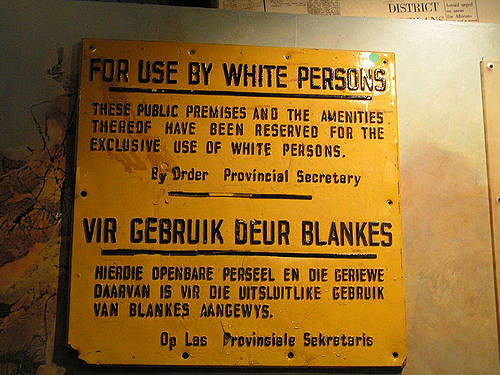

Initially, public pools were designed for young boys of all races. Once girls gained access, white adults objected to boys of color being around white girls. Cities made the public pools “Whites only”, and some white people would even beat people of color who tried to use the pool.

When the courts forced American public spaces to become desegregated after WWII, many cities simply shut down or filled in public pools rather than allow people of all races to swim. Pools moved into private clubs, which only allowed white members.

The end result of the cities’ policies around who can use public pools is that the overall drowning rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives is twice the rate for White Americans, and the rate for Black Americans is 1.4 times the rate for White Americans.

The community center offering classes for people of color to learn how to swim would help correct the results of the cities making decisions to exclude people of color from public pools.

Intersectionality

“But what about the poor white kids?” some folks might ask. “Weren’t they hurt when pools moved into private clubs?”

Yes, and no. Children from lower income countries are more likely to face drowning deaths than children from higher income countries. Around the world, WHO estimates that low- and middle-income countries account for over 90% of unintentional drowning deaths.

However, even when you take income into account, drowning rates in pools are the highest among Black American males. A study of Americans who died from drowning in pools from 1995 to 1998 showed that, “Seventy-five percent were male, 47% were Black, 33% were White, and 12% were Hispanic. Drowning rates were highest among Black males, and this increased risk persisted after we controlled for income.”

By offering free swimming lessons to children of color, the community center is choosing to focus on a particular group of people who are at higher risk of drowning. It’s no different than making sure older adults get tested for diabetes. There’s always a risk of children and teenagers developing diabetes, but diabetes is more prevalent in seniors vs children (25.2% vs 0.24%).

The question becomes, “How do we focus resources on the people who are more likely to need it?”

Lost Opportunity

That’s not to say white children in lower-income families don’t face a lot of issues. They often face food insecurity and the threat of becoming homeless. In fact, the neighborhood around the community center has a couple low-income housing units. The idea behind low-income housing is to offer apartments at a lower-than-normal rent, to ensure families can afford a safe place to sleep. Low-incoming housing in America is far from a perfect solution, but it is a step to address the problem of financial inequality.

When I was a college student facing another rent increase for on-campus housing, low-income housing frustrated me. I didn’t have a job, and my only source of income was scholarships or summer internships. Even if I took that income into account, I was still technically eligible under the income restrictions for low-income housing. However, every low-income apartment building explicitly banned students from applying.

I was annoyed by this, but it wasn’t the end of the world. I could take out student loans, and face the debt when I got a job. There was cheaper housing way out in the suburbs if I was willing to commute an hour by public transit into campus. I might be able to find a roommate who was willing to share my tiny studio apartment. If worst came to worst, I could move back in with my parents, consolidate my classes to two or three days a week, and commute by car for a couple hours each day.

The point is, I had other options. Some of them weren’t necessarily pleasant options, but I had more resources than most people whose income was below the poverty level. Just because I was denied access to low-income housing didn’t mean I was denied all housing opportunities. I just couldn’t access that particular opportunity, which was explicitly designed for people whose only other choice was moving into the street or camping out in their car.

The important question to ask is, “What is the impact of this lost opportunity?”

If someone can find another apartment, job, internship, conference, or event that fits them, it’s not discrimination to offer those opportunities only to people who would normally have a hard time getting access to those things. Instead, it’s correcting all the decisions other people have made that exclude people of color, people from low-income backgrounds, and people with disabilities.

Summary

It’s important to frame discussions of “reverse-isms” around statistics about who is more likely to face discrimination, how we can focus resources to help those people who are more likely to need them, and the real-world impact to people who benefit from diversity initiatives.

It’s important to acknowledge the lost opportunities people have when a diversity initiative isn’t designed for them, while emphasizing that those initiatives are there to correct historical and ongoing inequities that deny others opportunity. When talking to people about how the lost opportunity might impact them, it’s important to drill down into why they fear losing that opportunity.

Often the root cause is a fear of being excluded from a group, a feeling of being pressured to change in ways they don’t understand, a refusal to acknowledge discrimination exists, or a deep mistrust based on past experiences. Moving the conversation into a place where people can openly talk about those feelings takes a lot of patience over a long period of time. It involves managing the other person’s anxiety while gently nudging the person towards tolerance and acceptance.

If you’re curious, this post was written for people in the “defense” stage of the “Development Model of Intercultural Sensitivity” (DMIS). Judging where a person is on accepting other cultures is something that takes a lot of time and experience.

It often takes several interactions with folks at various stages of acceptance to recognize common misconceptions and pitfalls. It’s useful to consult with an expert who can help you create a plan to move your community or company into a stage where they’re more accepting of diversity.

Otter Tech is here to help with one-time or monthly advice sessions to help you make your community more inclusive.